Capturing the Limelight

Category: Features

l. to r.: freshmen Matthew Breyer and Lauren Linsao, students in the inaugural ARTS 297: Rehearsal Process and Performance Possibilities class; all photography: Chris Hartlove

New programs expand the reach of the University’s arts programs

The University of Baltimore has an established reputation for its professional schools, but its programs in the arts have often operated quietly, enriching the community of students and Baltimore without capturing too much of the limelight. That’s beginning to change.

Groundbreaking additions to the curriculum are expanding student opportunities for performance studies and classical music appreciation while grant-funded research housed in the Merrick School of Business′ Jacob France Institute is harnessing the power of data to quantify the impact and potential of the arts in the city.

The drive to expand and enrich arts programming at UB is supported by the Office of the President. When Kurt L. Schmoke was first approached about the presidency, his perspective on the school was mostly informed by his experience as a former Baltimore mayor who worked with the University’s law and business schools. As he considered the position and delved deeper into UB’s programs, he “was blown away by the range of offerings in the [Yale Gordon] College of Arts and Sciences,” he says. “I felt as though our arts and humanities programs were hidden jewels,” he adds.

Next-Gen Performers

The cast of One Particular Saturday reads through the script for the first time; Breyer (center) and freshman Elianna Clinton (right)

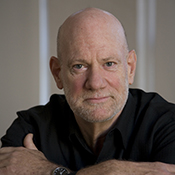

freshman William Smith; Kimberley Lynne, affiliate assistant professor; and Donald Hicken, director

As the father of two Baltimore School for the Arts graduates, Schmoke is particularly well versed in the importance of arts education and the complexities of building artistic career pathways. Of particular interest to him was the nascent idea of a pathway in the performing arts, an idea originated by Donald Hicken. The Tony Award-nominated director has been a prominent fixture on the regional theatre scene, but it was his more than 30-year tenure as chairman of the Baltimore School for the Arts’ Theatre Department that inspired his desire to build a performance training program at the higher education level.

“I had seen so many kids coming out of places like [the] School for the Arts, the George Washington Carver Center for Arts and Technology and other schools—talented kids who for one reason or another, mostly financial, didn’t have a lot of options in terms of college,” Hicken explains.

For those students, their aspirations for careers in the arts faded after high school simply due to a lack of affordable, accessible formal education within their reach. To stem this tide away from arts careers, Hicken envisioned an ensemble model of training wherein young people could access experiential learning and professional mentors.

“I had this idea, but the piece I couldn’t put into place was the educational piece—how are these students going to get a degree?” Hicken continues. “When Kurt Schmoke was appointed president, I thought, ‘Aha, now we have the perfect partner.’”

The new Performance Studies: Baltimore specialization launched this fall within the Yale Gordon College of Arts and Sciences’ Integrated Arts program. The specialization is one of the only in the area to partner with professional theatres for experiential learning; the Hippodrome Foundation and Everyman Theatre provide master classes featuring visiting artists and professional actor mentors. In addition to coursework, students have the opportunity to role-play an audition on the stage at Everyman Theatre, for example, and to get feedback from working actors.

“The city of Baltimore was bleeding out talent because there wasn’t a program here training anyone. We’re striving to keep the talent here.”

“They’ll be learning artistic techniques as well as some real practical nuts and bolts of how to make a career for yourself in theatre in America,” Hicken says.

At the conclusion of this first semester, Hicken directed the students in a performance of One Particular Saturday, about the 1968 Baltimore riots, at UB’s Wright Theater.

The partnership with Everyman Theatre and the Hippodrome Foundation is a differentiator for the specialization, and not just in Baltimore; organizers say it is designed to be one of the most unique college-level theatre options in the country. An entrepreneurship component of the specialization is also in the works to help students learn how to create and manage arts centers.

“At the core of integrated arts is arts management,” says Kimberley Lynne, affiliate assistant professor and arts and theatre manager at UB, who was integral to bringing the specialization to the University. “But we’re also reaching out more to the business school to develop more arts entrepreneurship curriculum so the performance studies students can learn how to build and maintain small arts nonprofits.”

By providing an affordable program to nurture young talent, the Performance Studies specialization not only extends an opportunity to young students but also fosters a sustainable arts community in Baltimore by building a local base of aspiring actors, directors and managers.

“The city of Baltimore was bleeding out talent because there wasn’t a program here training anyone,” Lynne adds. “We’re striving to keep the talent here.”

The Arts and Big Data

The Vital Signs 14 report, released in April, provides data on arts-related indicators for a number of specific Baltimore neighborhoods and also offers collective citywide totals for these same indicators.

Building a home for artists in Baltimore doesn’t just serve students and enrich the lives of residents; the arts and cultural opportunities more broadly can be a driver for community and economic development. While this has long been known anecdotally, the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance-Jacob France Institute (housed in UB’s Merrick School of Business) is turning narrative into data. Thanks to an Our Town grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, BNIA-JFI’s work will soon be accessible online in an innovative cultural mapping tool.

BNIA-JFI is a storehouse that uses data from city agencies and organizations to measure quality of life in Baltimore’s communities. More than 150 indicators—including everything from crime to income levels and dropout rates—are used. This information is released each year in the Vital Signs report. After a strategic planning session for BNIA-JFI in 2012, arts and culture indicators were identified as a missing piece of the quality of life picture.

“It’s part of our society thatʼs hard to measure quantitatively,” says Seema Iyer, associate director of the Jacob France Institute, “but we realized that we had to figure out a sustainable and useful way to track neighborhood vitality over time.”

Particularly as the city’s neighborhoods have become more diverse and secular, residents who may once have gathered around a church or hall are now more likely to come together in a public art space for a shared community experience. These experiences, which might include block parties or readings at a local library branch, were identified as strong indicators of quality of life through arts engagement.

The task of measuring these elusive factors fell to Christine Hwang, a member of the newly formed Baltimore Corps who was hired by BNIA-JFI to serve as an arts and culture fellow. She helped identify eight arts and culture indicators, including public art, public events, arts-based businesses and employment, and public libraries.

“A lot of times people think of art as something curated in a museum through a particular lens. This lets people express themselves and become known in their specific communities.”

“Arts and culture really measure quality of life, and it’s important to correlate these factors to things like crime and education,” Hwang says. “Also, through arts and culture data we begin to get an idea of where communities come together.”

The first year’s findings appeared in April in BNIA-JFI's annual report, Vital Signs 14. The data shows the areas that have the highest concentrations of creative businesses. It also identifies those communities that lack funded creative resources and are thus ripe for intervention and support.

The National Endowment for the Arts’ Our Town grant UB received is one of only 64 awarded nationally. With its $75,000, BNIA-JFI can continue to update its arts and culture data and also build a web-based, publicly accessible culture-mapping tool that will show the impact creative placemaking has on the city, help create a more equitable distribution of arts resources and heighten awareness of arts in neighborhoods outside the better-known arts districts. Hwang hopes the mapping tool will be useful for not only people in the arts but also urban planners and developers.

“It’s important because this is a way to track [public arts and culture], something that is accessible,” Hwang adds. “A lot of times people think of art as something curated in a museum through a particular lens. This lets people express themselves and become known in their specific communities. Also, a lot of our data is not always positive. This highlights something that's positive in all neighborhoods in Baltimore city.”

BNIA-JFI’s data already paint a picture of a vibrant public art scene in Baltimore. In 2014, for example, there were 1.2 works of public art per 1,000 residents, including 218 publicly funded murals. More than one in three Baltimoreans has an active library membership. The mapping tool is still in development, and there are plans to add a forum for uploading crowd-sourced material to the map so communities can participate in shaping it.

An Ear for the Arts

Hoover, a saxophonist and woodwind player, also composes new classical music and jazz.

Programs at the University of Baltimore aren’t just about mentoring tomorrow’s Tony Award-winner or helping an ensemble get the skills and knowledge to know where to locate their company and how to run it. They’re also about building a community of artists and art lovers who can live and work in a richly textured cultural community. An integral part of that placemaking is shaping the next generation of art appreciators, the students who will become patrons of the theaters, symphony halls, dance troupes and galleries.

“What you’re doing is supporting classical music immediately and directly. And you’re creating future audiences. It’s like planting perennial plants that will bloom on and on in the future.”

Thanks to a $100,000 grant from the Peggy and Yale Gordon Trust, students can expand their understanding of classical music through two new music courses: Introduction to Concert Music and Music for Dance and Opera. The classes align well with the Baltimore-based trust’s mission to advance classical music in the Metropolitan Baltimore area.

According to Jeffrey Hoover, associate professor and director of the Integrated Arts program, these courses meet student demand for more music offerings. They also underscore the value of classical music historically and in today’s society and address the issue facing classical music institutions of building audience participation.

“What you’re doing is supporting classical music immediately and directly,” Hoover says. “And you’re creating future audiences. It's like planting perennial plants that will bloom on and on in the future.”

The two classical music classes, which are open to all undergraduates, are not designed to put students on the stage as performers; they are about building musical literacy and appreciation so students can have a more meaningful experience in an audience.

“It’s important for people to have an opportunity to study various art forms more deeply and broadly,” Hoover says. “These two courses give us the venues and means where you would typically encounter classical music in our society—in a concert hall, [at a] dance performance or [at] a theater. ... It gives students a broader context and perspective over this concert-going experience.”

Music studies at UB are augmented by a live performance component. Classical artists showcased at Spotlight UB, the performing arts series overseen by Kimberley Lynne through the College of Arts and Sciences, also participate in classroom discussions. They provide valuable insight into their career paths, the performance experience and the music itself. This year’s guest performers-turned-teachers are renowned musicians including percussionist Peter Ferry, cellist Nickolai Kolorov, St. Petersburg’s Rimsky Korsakov String Quartet, Baltimore pianist Robert Hitz, and the flute and piano duo Rebecca Jeffreys and Alexander Timofeev. (The concerts are open to the public, though UB’s students enrolled in a classical music course attend for free.)

“Many students haven’t been to a classical music concert before or [to] a ballet,” Hoover adds, “so this is one small piece of the acreage that is growing some good ground for our students.”

As knowledge of the creative economy grows and creativity becomes intrinsic to all education, the University of Baltimore will continue to expand its programming in the arts.

“Humanities is not and should not be an afterthought in education generally and [in] higher education specifically,” Schmoke says. “I think most employers recognize that our graduates have skills in science and technology as well as a real appreciation for the humanities, which makes them well-rounded citizens.”