Features

UB Improves Its Energy Performance

The new "green" roof of the existing law center, complete with native plants in water-trapping trays.

What does an energy-saving future really look like? Some would imagine cleaner skies and better water, less extreme weather, an improved planet altogether. But most also think of deprivation: No grass in the front yard, uncomfortably warm or cold rooms and, of course, you can't use the car—ever.

But what if reducing our energy use was painless? What if the University of Baltimore cut back on its energy consumption by as much as a third (translating to $11 million in savings over the next 15 years), became a greener institution in the process ... and we hardly even noticed it?

That process already is well underway, through the aegis of UB's Energy Performance Contract with Energy Systems Group. It's a multiphased, multiyear, campuswide effort to tap into new and evolving technologies and maximize our energy efficiencies—with only a smidgen of pain and a relatively low investment. In less than a year, the University has enacted a number of significant energy-savings measures, including skylights and photovoltaic panels on the roof of the Academic Center as well as water- and heat-capturing plants on top of the current John and Frances Angelos Law Center. And there's more to come—just ask Steve Cassard, vice president for facilities management and capital planning at UB. He's a strong advocate of true management of the University's energy needs, even in this time of rapid campus growth.

Cassard is not a zealot for deprivation—he's a common-sense guy who knows how to save energy. And his goal is to do so quietly, sensibly, without asking the University community to give up the things we need to teach, learn and do our jobs.

"Big energy savings at UB can be practically seamless," Cassard said recently. "It doesn't have to hurt. We can turn off some unnecessary lights and reduce the amount of water flowing through our pipes, and for the most part it is hardly noticeable. Based on what we've done so far, we're well on our way to reducing our usage by a third by next year."

Karen Galindo-White, UB's chief liaison at ESG, concurs.

"There is even more that can be done to save energy without much of a sacrifice, but every campus setting presents challenges and opportunities when you're dealing with sustainability and efficiency," Galindo-White said. "At UB, we've had a relatively easy installation of energy saving devices, but as you do more, the gains come in much smaller increments."

Still, the initial forays into energy reductions have been impressive: They are well above Maryland Gov. Martin O'Malley's goal of achieving a 15 percent drop in statewide energy usage by 2015.

But what has UB done, exactly? There are no windmills in Gordon Plaza, no odd restrictions on when you can turn on the power. Where are the savings coming from?

"We've installed smarter lights that go off when a room is empty and improved our plumbing fixtures so they don't waste water," Cassard said. "That's pretty low key. It's amazing what you can do by upgrading your equipment, updating control systems and that sort of thing. Just putting in weather stripping along doors and windows has a measurable yield. That's the everyday, homeowner kind of thing and it does work. But we're also tackling bigger initiatives, and so far we've had a lot of success."

This past summer, for example, ESG installed skylights and photovoltaic panels on the roof of the Academic Center. The skylights allow natural light to flood into the Center for Recreation and Wellness on the top floor of the building, eliminating the need for high-wattage lights on sunny or even partly cloudy days.

"That space really benefited from skylights," Cassard said. "Now it simply doesn't need all the lights on all the time for some number of days out of the year. And because it's natural light, it's more pleasing to the eye. You're playing basketball or volleyball on the court there, and you get a little sunshine. It's nice."

And it saves. The solar panels also do their share. They capture sunlight and convert it to electricity, which UB delivers back to the electrical grid. This figurative "dialing back the meter" cuts the University's power bill and also reduces the amount of electricity generated by carbon-producing sources.

In addition, there's the green roof on the existing law building, which is made up of trays of native plants and grasses laid out on an impermeable surface on the roof. It creates a shield that helps cool the structure in summer and hold in heat in winter. The plants also absorb rainwater that otherwise would be shed from the roof, and, eventually, into the Jones Falls and then the Chesapeake Bay.

You can see these installations by taking a walk up to the top floor of the UB Student Center and looking out the windows facing Mount Royal Avenue. But another major efficiency tool is completely tucked away from public view—the control systems that help regulate the use of energy much more efficiently than a person with a switch could ever hope to do. These devices are not exotic, but they do a lot of heavy lifting when it comes to energy efficiency.

For example, a chiller system cools down water like a refrigerator—but it does so during off-peak usage hours when electricity is cheaper. The chilled water is stored overnight, then pumped back into the system when it's needed to keep rooms cool. New, smarter boilers do essentially the same thing, only they're raising the temperature when we need it.

"Again, it's doing the work for us, but you don't notice that you're saving until you get the bill," Cassard said.

Nothing is escaping the eye of UB's energy reduction crew—even the coming outdoor signs that let passersby know they're on the UB campus will make use of wattage-saving LED bulbs.

"You look for savings wherever you can find them," Cassard explained. "Little things add up. And the LEDs are going to be very attractive, a real step up for us."

At some point, UB will maximize its efficiencies when it comes to energy usage. But the campus—an early signatory of the American College & University Presidents Climate Commitment back in 2007—seems ready to keep pushing to a "carbon neutral" stance. Students, faculty and staff, through the UB Sustainability Task Force, continue to come up with new ways to go green, through recycling, carpooling, public transportation and living within walking distance of campus.

A carbon-neutral UB would mean that overall, we are saving as much energy as we're using on campus, by reducing our dependence on carbon emitting fuels and tapping into renewable sources as much as possible.

According to Galindo-White, these next steps may involve some challenges, because they will require the campus to become even more active and committed—something closer to the zealot model.

"To move people from neutrality to action on this issue will require making it real to them," she said. "If people understand the consequences of turning on and leaving on lights, for example, then perhaps they will make a commitment. You have to be willing to change your life somewhat, as a member of a larger community. Some might see it as hardship—each person defines that concept differently. But at UB you have started down this road, and that is inspiring."

Cassard agrees.

"Look at all that we've done in the course of a year," he said. "We can do even more; we have momentum on our side. Whether you're into cutting your bill or saving the planet, let's keep going."

Read more about the Energy Performance Contract and UB's commitment to sustainability.

UB Rediscovers (and Reworks) Its Official School Song

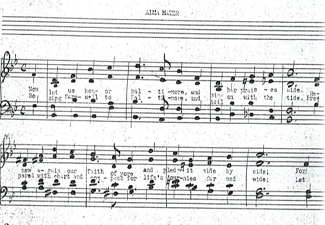

The original sheet music and lyrics for the University's official school song.

Restarting a tradition that goes back decades, the University of Baltimore has brought back its official school song, the "UB Alma Mater," and is teaching it to the newly entering Class of 2013 as well as other undergraduate and graduate students.

The song—a handful of lyrics and sheet music discovered in its Langsdale Library archives by Robert Pool, now a reference librarian and faculty liaison in the UB School of Law Library—dates back at least to the 1950s. Pool first saw the sheet music when he worked in Langsdale's archives in the 1980s, and showed it to various UB officials including Thomas Hollowak, associate director of Special Collections for Langsdale. At the time, no one at UB could recall the song or when it was played, but to Pool and Hollowak it had the earmarks of an official song.

"We haven't been able to identify the author, but it could be based on an old church hymn," Pool said. "Some at UB can recall a UB pep song or fight song, but this is not that—this is a serious, orchestral sounding work. It's actually not bad as music, better than some other alma maters I've heard."

Pool has conducted queries into the author of the song, but so far no clues have turned up. He hopes that the more people who hear it, the better the chances of locating someone who is familiar with it so that its copyright can be determined.

"I see playing it in public as part of our due diligence," he said.

Pool, who has a background in music theory and composition, hasn't stopped there. He recently used a piece of software called Sibelius to virtually orchestrate the "UB Alma Mater" sheet music, transforming it from notes on a dusty page to a robust piece with old-school touches. Inspired, he is now working on some variations on its theme.

(See the sidebar below to learn more about Pool's ongoing work on the orchestration.)

The lyrics, which refer to the University only as "Baltimore," feature lines about the power of education:

For vision bright of wisdom's light,

For gift of wings to soar,

For teaching us the might of right,

We thank thee Baltimore.

Pool said a note attached to the sheet music called for it to be played in the key of G.

"That's a pretty important notation," he said. "Play it in the wrong key and it's very hard to sing."

UB's incoming freshmen practiced the song during last month's Access UB event, and then performed it for the entire student body at the Lyric.

Catch a YouTube video of the song in performance. See the original lyrics page and the sheet music from Langsdale Library Special Collections (PDF).

Arranging the 'UB Alma Mater'

Article by Robert B. Pool

When we hear many pieces of classical music, often a number of the melodies are not actually written by the work's composer, but come from other sources. For example, one of the fundamental melodies used in the Finale movement of Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 4 is actually a Russian folk tune he "borrowed." I didn't realize this until, when playing a recording of this for a friend, she heard the tune and said, "Oh, that's the famous Russian folk song, 'In the Field Stood a Birch Tree.'" So, in this sense, many composers can, to an extent, be thought of as arrangers of extant music.

That was my intention when I was asked by our Rosenberg Center for Student Involvement to expand the very basic orchestration of two repeats I did for the "UB Alma Mater," so that it repeats six times with slightly different instrumental combinations, the last two for full orchestra. This was done to keep it interesting, and to have it repeat often enough so that our students would learn the melody and sing the lyrics.

In the past, all of this work would have been done with just pen and score paper. You would have to deal with instrument transpositions then and there, among other things, such as already knowing what each instrument's range is. Certain instruments have music written for them in keys different from most instruments: french horns are considered to be in the key of F; the standard clarinet is in B flat (although there's a smaller version that can play higher notes), and so on. Fortunately, a piece of software called Sibelius helped me work out all of the problems associated with bringing new life to this old song. More about that later.

Admittedly, the "Alma Mater" had some requirements that were limiting: The melody had to be the primary element that listeners heard, especially since we wanted them to quickly pick up the melody. This eliminated the possibility of modulation, which is a departure from the primary key of B flat and a repeating of the melody in other keys. Composers use this technique to keep the same melody from becoming boring upon repetition. Also, I could not create too many musical embellishments or other variations that could distract our singers from the primary melody. (Still, if you listen carefully, there are some embellishments and alternate musical lines playing against the overall melody—but they're written so as to not overshadow the melody.)

The idea of a theme and variations on the "Alma Mater" is a project in the works for me. Themes and variations have long been a standard musical form in classical music, and this piece lends itself to any number of colors, from playing the same melody in waltz form or in other tempos, to playing it in a minor key as opposed to the major. It's also possible to turn the melody "upside down," (inverting), or using the opening bars as a departure point for a classical music form known as a fugue.

If you know the original Disney film Fantasia, the opening work is the Toccata and Fugue in D minor by J.S. Bach. A fugue in a musical context has a meaning akin to "running away," so a composer can take a basic melody and repeat it in various ways that sound like he or she is fleeing with it or from it.

I might not run off with it, but I could change the"Alma Mater"'s harmonies in ways you might not expect—the impressionistic styles of Debussy or Ravel might be effective. While the song overall has its limits, experimenting within its confines is fun and interesting.

A little more about composing and arranging with the little electronic wonder called Sibelius: When you're writing music, you need a "home" key, around which any piece is created. This home key is said to be "concert pitch." If you play the note "C" on a piano, it is considered to be in concert pitch. If you write the same note on a piece of music paper, it prompts the pianist to play a C. This is also true of the violins, violas, cellos and basses in the string section, as well as the flutes, oboes and a number of others. But because the B flat clarinet is a transposing instrument, it doesn't work in quite the same way. If you write down a C and ask a B flat clarinetist to play it, the note you hear won't match the C on the piano. Instead, you'll get the next note up, a D.

The software also eliminates the confusion of writing music in several different keys at the same time. You choose the concert pitch key you want, and you write for all instruments as if they were in that same key. When you're finished, just click on the "transpose" button, and all the transposing instruments are converted into their proper key.

As you can tell, it's complicated. Fortunately, computer software has made the life of arrangers a little easier. The Sibelius program is popular with professional musicians, composers, score writers and arrangers. Much of the technical information that you must have in mind while you're working has been made relatively painless by Sibelius. It's considered a music version of a word processing program. For example, if you enter notes into the program that exceed the limitations of the instrument you've selected, it inserts them into your score in red. Or you can highlight the melody being played by a whole section, such as the brass, and then copy and paste that into the score just behind it—but this time in the woodwinds or strings. It speeds up the process tremendously.

You can even hear what the music actually sounds like while you're composing. This tells you, in no uncertain terms, if you've made a mistake along the way. I use a SoundBlaster Audigy soundcard in my machine so I get a true representation of this first pass at the evolving score. As I worked up the "Alma Mater" rendition, I used an instrument set called the "Garritan Personal Orchestra."

So, by virtue of modern technology and a willingness to invest in the software, you can write music for virtually any kind of assembly of instruments you want. You can have your own full orchestra at your disposal, and actually hear the music you're writing on the fly.

My primary interest is the vast repertoire of orchestral music, so over time I have come to experience music in that context. It's not difficult for me to "hear" orchestral arrangements in my mind, and even apply the standard orchestration devices as well as the potential clichés to a piece of music I've never heard before. I inserted a little joke into my orchestration of the "Alma Mater"; listen to the last note for a cliché on how most 19th century romantic era orchestral works ended.

If you want to hear the orchestration of the piece, check out this .wav file, which is available on the Langsdale Library's Special Collections Web site.

Robert Pool is a reference librarian and faculty liaison in the UB School of Law Library. He has a background in music theory and composition.